There she was again—that face. I’d seen her many times, in many different situations and clothes, always playing as if she were someone else, always successfully hiding beneath a glamorous facade. But I always saw through her disguises to the person she really was. I always saw the real Marsha Hunt. Or did I?

Of course, as a child I didn’t think anything of the sort, and childhood is where my relationship with Marsha really began. I just thought of her as “the pretty lady.” At first she was just one of the beautiful soft-focus faces I religiously watched on afternoon and late- night television. Many nights, after my parents had gone to bed, I would creep out from under my covers and into the living room where the console television was waiting, a co-conspirator in my nocturnal viewings. I would turn the sound down low and sit as close to the screen as I could and still be able to see the image. I loved the old black- and-white movies and the people who inhabited them. I knew which number on the dial was the key to the kingdom they called Hollywood. I started noticing the faces of certain stars I preferred, long before I knew their names. Marsha was one of those faces. What I noticed and loved about her was not only the beauty, with wide-spaced blue eyes and a profile like a notebook doodle, but also the physical grace with which she carried herself, often to humorous effects. She could faint gracefully into a spinning swoon or dance with her feather duster as she cleaned the furniture in a room. She could run across a moonlit garden in high heels and evening gown without tripping or even seeming aware of her feet. I thought she was wonderful. Gradually I started to see her in primetime places other than movies as she appeared in episodes of TV shows like The Twilight Zone and Outer Limits, and one summer in the 1950s, I was thrilled when she played the perfect mom in a witty comedy series called Pecks Bad Girl with killer kid Patty McCormick. It was with these TV appearances that I learned her name was Marsha Hunt. After that, she became a face and a name I always watched for. Anytime I saw her name, I made a point to watch. I never lost my taste for the movies that Marsha and her contemporaries made. Without my realizing it, they were becoming the basis for my future.

Many years passed during which I left home, went to different schools and became a New York City-based illustrator and then hopeful doll designer. At this point all these hundreds of movies I had watched over the decades came flooding back to me as the basis for the fictional lifetime and career of my creation, Gene Marshall. I set Gene’s story squarely in the period I loved the most and created a composite of my favorite stars who had helped form my ideals of beauty. That Gene’s last name was Marsha with two letters added at the end went by unnoticed, even by me.

During the early blush of Gene’s success I was introduced to Marsha once again in the most fortuitous way possible— through her wonderful book The Way We Wore. My friend Doug James had a copy. One day, as we were discussing a possible dress design for Gene, he showed me Marsha’s book as reference. I was thrilled! For some reason I hadn’t known about the book until that moment. Instantly I did a bit of footwork and found myself a copy—and then a few more copies. The book became a treasured source among Gene’s designers for any number of the costumes that went into the Ashton Drake line for Gene. Even when the specific outfit wasn’t from the book, how it was worn and with what certainly was.

During the early blush of Gene’s success I was introduced to Marsha once again in the most fortuitous way possible— through her wonderful book The Way We Wore. My friend Doug James had a copy. One day, as we were discussing a possible dress design for Gene, he showed me Marsha’s book as reference. I was thrilled! For some reason I hadn’t known about the book until that moment. Instantly I did a bit of footwork and found myself a copy—and then a few more copies. The book became a treasured source among Gene’s designers for any number of the costumes that went into the Ashton Drake line for Gene. Even when the specific outfit wasn’t from the book, how it was worn and with what certainly was.

A couple of years after discovering Marsha’s book, I was approached by Hyperion Press to write and illustrate a book of Gene’s biography. One of the concepts we decided upon for the book was to ask a few real celebrities to write their memories of the early rise of our girl star as if she had been real and had affected their lives. I immediately thought of asking Marsha to contribute a piece. After using so many of her costumes for Gene, it seemed the perfect connection. Gene had been a model early in her career, just like Marsha, and I had noticed by then other similarities in their stories. So, through a dear friend of mine on the west coast, Gene Maiden, I sent an extremely heartfelt letter to Ms. Hunt, asking if she would consider writing a few sentences for Gene Marshall, Girl Star, the decided-upon title for my book. To my absolute joy and amazement, she agreed. In a few weeks, two wonderful pages arrived from Marsha. They were a lovely account of a studio commissary meeting between Marsha and Gene, beautifully written and extremely generous to the story I was telling. A flurry of faxes went back and forth, and she received enough thank-you flowers from me that she wrote to tell me to “stop with the flowers.”

She assured me she had a beautiful garden behind her home and was really worried about all my money going into her vases. During this phase of our friendship, based entirely on phone calls and faxes, good luck intervened and Marsha was invited to New York to speak at a tribute for film director Jules Dassin. We arranged for a lunch meeting during her stay, and on July 6, 1999, we met face to face for the first time.

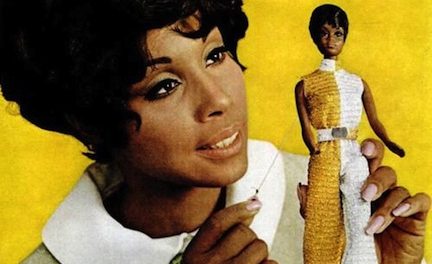

After our three-hour lunch, I came away smitten and have remained so ever since. With the book completed and a success, I was able to take some time and travel to California occasionally and spend time in Marsha’s garden and lovely home and realize a life-long dream of actually being friends with her. I wanted to share this lovely friendship with the world, so I proposed to Ashton Drake we step outside of Gene’s usual story line and create a doll entitled “Mel Loves Marsha.” I had a beautiful Irene-designed gown from The Human Comedy meticulously copied, and we coifed the doll in a style reminiscent of Marsha’s famous “feather cut.” “Mel Loves Marsha” was one of the most successful dolls from the 2004 line.

At the same time “Mel Loves Marsha” was being planned for the Gene line, I was working with Sandra Stillwell on arrangements for the ninth Annual Gene Convention, planned for the Biltmore Hotel in Hollywood. After Marsha agreed to be the guest of honor, Sandra and I plotted for that year’s convention to be a tribute to “all things Marsha.” There was a competition of Gene-sized fashions, taken from The Way We Wore, with Marsha facing the impossible task of judging. I can only imagine the surreal aspects of seeing your own past created in miniature and requiring an official favorite. We showed the wonderful movie Lost Angel that Marsha made with film (and doll) legend Margaret O’Brien, and a room full of fans got to watch Marsha watching herself. We decided the souvenir doll would be dressed and styled in a beautiful white and gold dinner suit design by Travis Banton and borrowed from the film Smash-Up, Story of a Woman. A group of individual souvenir outfits were designed that year, all based on Marsha’s wardrobe, including the lovely fur-trimmed pink suit in which she had been happily married to Robert Presnell. It came with a striking floral and tulle hat and bridal bouquet and was certainly a sentimental favorite with Marsha. As she effortlessly charmed the crowds and announced that she had just celebrated her 87th birthday, I swore to myself that I’d throw her another party on her 90th.

This year’s Gene convention is just that party: the chance of a lifetime to celebrate a lifetime beautifully lived. When I first realized the year was upon us, I asked Marsha if she was up for another birthday party. When she gave me the enthusiastic go ahead, I presented the convention organizers with the idea— make the convention a 90th birthday party for Marsha and a tribute to and 60th anniversary for her film noir classic Raw Deal. I put the two occasions together and named the convention “Rare Deal.” We went into high gear with plans to create a tribute doll for Marsha that would complement the earlier dolls, yet be distinctively different. We decided for the first time ever in the Gene line to sculpt a portrait head of a real individual and create a true Marsha Hunt doll.

We went back to the original sculptor of Gene, Michael Evert; for four weeks he and I worked from countless studio portraits of Marsha and prepared the new head. Bits and pieces flew back and forth from the factory as the doll quickly took shape. We selected the clothes from Marsha’s book again: a gorgeous Edward Stevenson-designed black-tulle-over-flesh evening gown and a sporty tennis dress for the two dolls. Our separate outfit became a sensational fur-trimmed suit and hat designed by Edith Head, featuring such period innovations as a decorative silver zipper closure in the front and detachable fox peplums. When you’re interpreting fashions by such revered designers as these, you keep your fingers crossed and your heart in your throat.

There’s an age-old storyline in Hollywood that says two stars can’t happily share the same spotlight. Gene Marshall’s own story is based on her rivalry with Madra Lord over just that issue. But this year, at the 12th Annual Gene Convention, this timeworn cliché is being proved out-of-date and no longer valid. Gene Marshall and Marsha Hunt will be there, hand in hand, sharing the same spotlight and loving every minute of it— both of them perfect examples of what happens when love turns to vinyl.